While we typically associate utility locating with modern times, one recent GPR survey in Nova Scotia has located buried infrastructure from Canada’s early colonial period.

French families – Acadians – began moving to the rural community of Grand-Pré in the beautiful Annapolis Valley in the late 17th century. Their community came to a horrible end in 1755, when, during the lead-up to the Seven Years’ War, Britain’s colonial government deported the inhabitants. Mapping their destroyed settlements is now a task for archaeologists, and GPR is a valuable tool in their toolkit.

Based on the artifacts found at the site, the survey area appears to have been an Acadian house. Colonial-era homes generally had shallow root cellars with some having drystone walls, while others were simply dug into the subsoil with sloping sides to prevent slumping and collapse. With the building’s wooden superstructure long gone, the best archaeological evidence remaining is usually the old root cellar, often crammed with debris.

Using a NOGGIN® 500 SmartCart by Sensors & Software, GPR data were collected over a grid of 30 x 40 m (1200 m2) with a line spacing of 50 cm and a step size of 2 cm in both x and y directions. Data were then processed using the SliceView module in the EKKO_Project GPR analysis software.

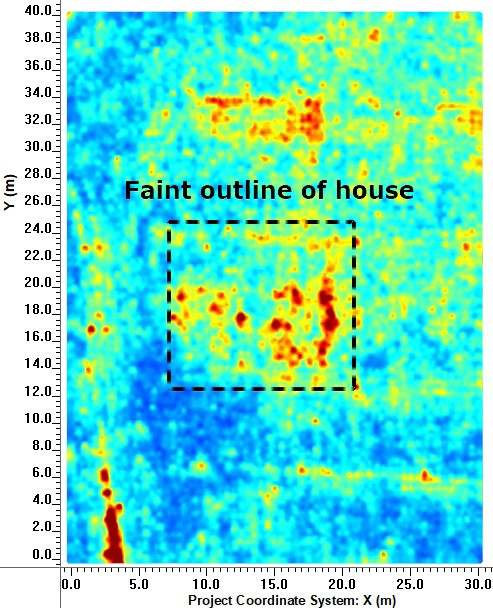

At a depth of about 15 cm, the building’s stone footing is revealed by a familiar rectangular plan (Figure 1). Colonial houses were not always set on foundations, but the data suggest this one was, and that it has largely survived intact despite over 250 years of farming activity at the site since the house was abandoned.

The most prominent features in the data are agricultural drains installed in the early 1970s, which can be seen running from left to right at regular intervals across the grid area. Two pipes can be seen in Figure 2 and three pipes trenches in Figure 3. The more archaeologically interesting features are seen between these drain lines.

Slightly deeper, two interesting rectangular features appear in the data: an area of low reflectivity and, adjacent, a zone of more reflectance (Figure 2). Both have architectural significance. The area with no reflections is an area of signal attenuation such as one would expect in soils dominated by clay. Architecturally, either a tamped clay floor or elements of the clay-rich fireplace and oven complex could be responsible. The highly reflective square patch, likely caused by stones and other debris, to the right of the clay-rich patch soon resolves itself into a cellar.

Furthermore, near the base of the cellar and leading out to the upper right of the survey grid, a slightly curving reflective feature was seen (Figure 2). It runs perpendicular to and at the same depth as the agricultural drains, suggesting the construction of the cellar drain that is unrelated to this 20th century infrastructure, and that these later intrusions may have impacted the older structure in place.

The cellar drain appears to run nearly to the upper edge of the survey grid for about 22 m (Figure 2). It was set into a trench measuring approximately 60 cm wide and excavated to a depth of just over 1 m. That required a lot of digging, but it was no great chore for our colonial-era ancestors, for whom prolonged bouts of physical labour were a daily fact of life. It was dull iron shovels and determination.

This drain was probably a channel lined and capped with carefully selected fieldstones; based on previous ones that were excavated in the neighbourhood. Some drains are still working centuries later, despite having been half clogged with burned debris from the house that formerly stood overhead.

What is fascinating is that when we slice down through the layers in the GPR data, we can not only see the drain itself, but also the outline of the trench into which it was set (Figure 3). This linear feature of low reflectance is a result of the natural soil layers having been broken up by the builders.

The mixed fill of the construction trench, no longer exhibiting its natural stratigraphy, now contrasts with more reflective soil layer boundaries around it: yet another instance in which a void in the data offers clues to past events.

GPR systems are adept at locating utilities in a variety of modern settings and have become a standard tool of civil engineers and technicians. They are also a powerful and welcome addition to the archaeologist’s toolkit enabling them to identify subsurface features at varying depths with the use of a powerful yet simple data visualization tool like depth slices (Figure 4). Therefore with the proper methodological and theoretical grounding, archaeologists can use GPR to locate more ancient utilities and map archaeological sites.

Story courtesy of Dr. Jonathan Fowler, Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, and Northeast Archaeological Research Inc.

Learn More about GPR for Archaeology